#6 Where does the river flow?

The seen and the unseen challenges to river ecosystems in India.

While a frothing Yamuna is visible and captures our attention every once in a while, there are bigger challenges that threaten the river ecosystems in India that go unseen.

This week, images of devotees taking a holy bath on Chhath puja in a frothing Yamuna grabbed headlines. There was some outrage and soon another set of images emerged - of Delhi Jal Board trying to clean up the froth with boats and nets. These temporary and ineffective measures will also be given up soon as another disaster will strike, and we will move on to outrage on that.

A quote from the book “In Service of the Republic” summarizes the situation well, “We work through panic, package and neglect.”

There is more or less apathy over the situation. “Ye to hota hi rehta hai.” (This happens every year.. ) and so we carry on.

A case for environment regulation

There is also a non-significant number of people who would go so far as to justify the situation as a price to pay for development. The narrative has been going on for a while now - environmental regulations are a cost and would make industries less competitive. So if we want Indian manufacturing to flourish, we will have to compromise on the environment.

This is a very misguided understanding of market theory. Pollution is categorized as a “negative externality” in economics - something that is created by one entity, but its negative effects are borne by someone else. A factory will always have the incentive to save costs and release untreated effluents, while it is the society that has to bear its harmful effects and it is the State (which is funded by public money) that is left to do the cleaning up. The only one who has the power to police the situation is the State, and the best mitigation is proper treatments of effluents that reduces their environmental impact. This makes a strong case for environmental regulations.

While this may sound elementary, I am outlining this because somehow we are veering towards looking at environment regulations as roadblocks to development. We can safely say that this is more or less the government’s stance too, where the environment ministry is chasing “ease of doing business” rather than compliance.

An IndiaSpend report states:

“Between early 2015 and late 2017, state pollution control boards, on instructions from the Centre, have exempted 146 of 206 classes of polluting industries from routine inspections...This change has allowed units in sectors such as coal washeries, stone crushers, fly-ash disposal, railway sidings and food processing - many with a poor track record of compliance - to operate without direct regulatory oversight.”

The Seen and the Unseen

( I borrow this phrase from podcaster Amit Varma, who borrows it from economist Frédéric Bastiat. )

Pollution is a well acknowledged problem affecting rivers in India. Due to its visibility, it at least gets occasional attention as well as some level of awareness amongst the society for the need to do something about it. However, there are many other challenges that threaten our rivers, but there is hardly any public attention or understanding on these issues because they are unseen, at least to the common citizen.

Thankfully there is a lot of grassroots work being done by civil society organizations that throw light on these issues. India River Forum is an umbrella of such organizations, currently organizing India Rivers Week 2021 - you can register at the link here. Their recorded webinars are available here. They bring together distinguished panelists - scientists, researchers, grassroots activists and bureaucrats - who share their work and insights on these issues. While it will be best to listen in to the webinars, I will attempt to summarize major points here:

Over damming of rivers - All major rivers in India are heavily dammed. While we hail the hydropower projects as a green alternative to coal power plants, mega hydro projects also cause significant damage to the rivers due to obstruction of natural flow and fragmentation of habitat, which compromises the river’s ability to perform its ecological functions.

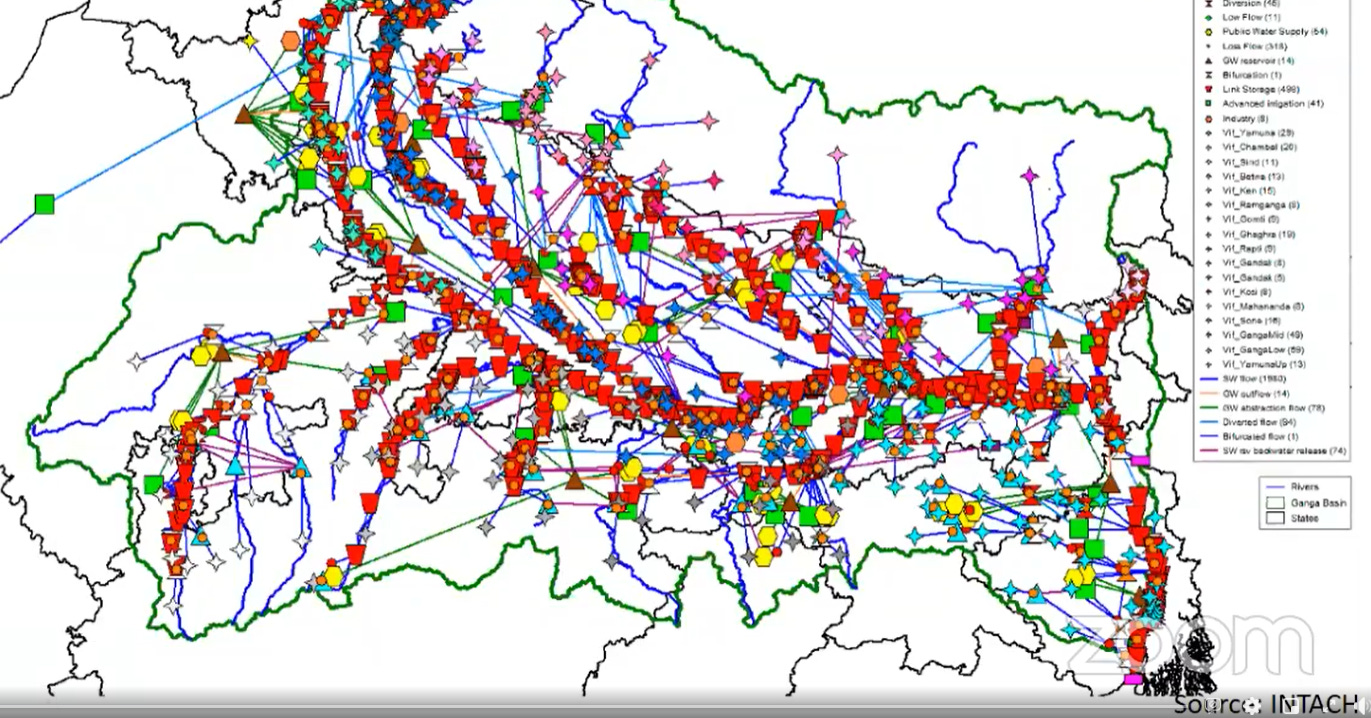

The scale of this is also not understood well. When environmentalists talk about “over-damming” a layman’s impression is often along the lines of “oh, these people have to oppose everything”. But if you would care to read the details, the numbers are astonishing. A report released by INTACH states that there are 1000 dams, barrages and hydroelectric projects on the Ganga basin and its tributaries alone. Below is a snapshot of the presentation done in the webinar2 of India Rivers Week 2021, showing the dams, barrages, navigation channels and other infrastructure on Ganga. ( This is created by INTACH. I will update if I find a link to the report. ) It is a dense network of infrastructure that leaves very few stretches for the river to flow without obstruction.

Effect on fisheries - When river habitats are fragmented, fishes and other aquatic animals cannot move freely to their breeding grounds. Many marine fishes also have to travel inland to breed. The numerous barrages and check dams built on rivers stop this natural migration path. They also obstruct or divert a majority of water to either reservoirs or for irrigation use, leaving very little environmental flow in the river. River habitats and breeding ground near estuaries are adversely affected by this as these areas turn hyper saline due to lack of freshwater. Fish catch in rivers has been reducing - this not only affects the fishers, but it also has a direct impact on locally available nutrition for riparian communities.

Inland waterways - This is another upcoming threat to rivers. In 2016, 111 rivers were nationalized, opening them up for Inland waterways development. This entails plying of barges that often carry coal for power plants and are polluting themselves. The dredging and noise pollution caused by them also affects the habitat of fishes and aquatic mammals like dolphins. There are inland waterways planned in dolphin habitat in Ganga and Brahmaputra basin. Here’s a detailed report by Down to Earth on this topic.

Encroachment of floodplains and wetlands - Sand mining, encroachment of floodplains and wetlands not only interfere with the natural processes of the river ecosystems, but also cause avoidable disasters that we have witnessed in recent years. The disastrous flooding in Chennai is attributed to construction in floodplains and wetland areas of river Adyar. (Here) Zoning laws and leaving buffer spaces to absorb excessive flooding should be a no-brainer solution. But it has been overlooked for many decades and continues to be neglected.

So what is the root cause of these issues?

At the core of this is the fundamentally flawed lens we apply to rivers. In popular culture and rhetoric, we may be praying to rivers, however, in reality we see rivers only as a source of water. But a river is not just its water.

In the India River Week’s first webinar, one of the panelist, Mr. Paritosh Tyagiji (ex-CPCB) explained this well.

“A river is a living ecosystem that performs various ecological functions and needs an ecological flow to sustain itself. But this critical difference is seldom in the minds of the people who propose and implement projects over rivers.”

This gap in understanding results in the fact that while we acknowledge and account for demand of water for drinking, irrigation and industrial purposes, we fail to account for the demand of the river to perform ecological services like supporting flora and fauna, fertilizing the river plain and recharging groundwater.

When it comes to dams and irrigation, we almost think of rivers as giant pipes. “Aree.. the water flowing into the ocean is getting wasted”, this is a common line of thinking. ( I subscribed to the same thought process about two decade ago while Narmada Bachao Abhiyan was going on. I was a teenager then. My understanding has changed over the years as I have followed the issue more closely. ) Because we see rivers only as pipes, we think we can move its water as we please. Grand plans like river-interlinking projects arise from this unidimensional engineering approach.

Disconnect between people and the river

Not only bureaucrats, most of the well meaning citizens also share the same views. We do not know where our drinking water comes from and where our drainage is being emptied. So rivers are no longer an issue that matters in our daily lives. Although they do impact the lives and livelihood of millions, it’s a second order effect for most of us, and so it remains unseen.

With such limited understanding on the issue, it fails to become an issue we vote on. Politicians also find it much more fashionable to showcase large hydropower plants or riverfront beautification projects that can provide grand inauguration opportunities in election season.

So what is the solution?

Let us try to apply the basics of public policy to this problem. So what kind of market failure happens with rivers? Rivers are “rival” resources - water allocated upstream is no longer available for those downstream. At the same time they are not “excludable” (in most stretches). This fits the definition of what is called “Common goods”. Issues of rivers can be termed as the “Tragedy of the Commons” - everyone has the incentive to consume the resource at the expense of the other, with no way to exclude anyone. This ultimately results in the depletion of the shared resource.

The textbook solutions to this problem are :

Establishing private property rights over public goods - Potentially this can be done by dividing fishing rights or water rights between communities over river stretches. Though honestly, I have doubts about implementation of such solutions in context of rivers.

Government regulation - This may very well work for polluting industries and municipalities dumping untreated sewage into rivers. Right now we have regulations, but compliance is missing. That will only happen when there is political will due to social pressure.

Collective actions by communities - Communities can figure out a self-regulating mechanism to maintain the shared resource, once they feel that it is in their best interest. Traditionally many fishing and forest dwelling communities have been able to devise ways to self-regulate. Though broader communities like villages and cities are yet to reach that level of awareness about rivers. Many countries are actually decommissioning their dams and hydro power projects, and setting up river reserves.

Again, all of these require regulation from the government and some form of collective action from the society.

So, am I hopeful about this? I don’t know. I would like to end with this quote I came across in the comments section of this Youtube video. It was posted by the director of the video.

The comment said,

“....Optimists think everything’s going to be fine, no matter what happens, and they excuse themselves from action. And pessimists think we’re f**ked no matter what happens, and they excuse themselves from action. But hope lives in the unstuck middle place where agency is possible.”

P.S: I also happen to have made a full comic titled “Where does the river flow?” on this topic. Do check it out here.

References:

Toxic foam coats sacred river in India as devotees bathe in its waters

How Government’s push for ease of doing business is compromising Environment Regulation

1,000 dams on Ganga basin obstructing tributaries: Study

Killing the Ganges river Dolphin, slowly